A VOICE ABOVE THE MAELSTROM

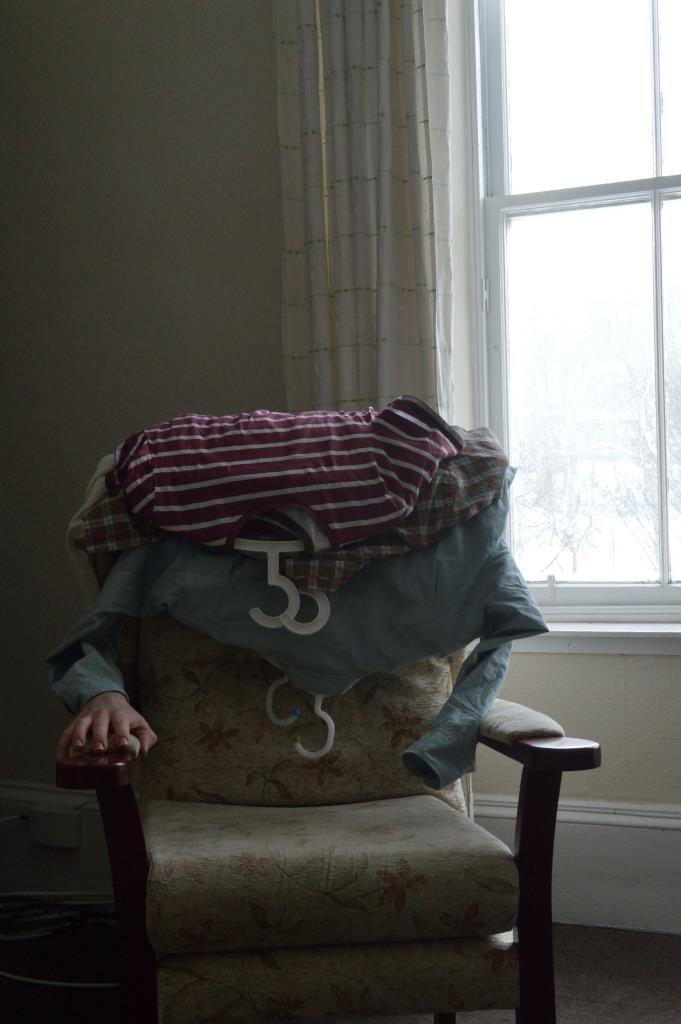

Hallo again. Welcome to Echo, the last of our Changeling trilogy and the latest of our online issues. As you are no doubt aware these are very Abridged times, turning us into slightly warped facsimiles versions of ourselves. We are voiceless in the face of something vast and spiralling as we search desperately for the stories that define us, that mirror ours, that echo ours. All we can do is try to keep our head above the water and be the best versions of ourselves possible. If there’s still a best version of ourselves to be.

So where’s the Contents list? There isn’t one. Think of this incarnation of Abridged as a fog where you only see the outline of objects potentially friendly and some things perhaps not so friendly, as you slowly edge towards what ever it is you define as familiarity.

We’ve attempted to keep the esoteric spirit of the print edition rather than create a straightforward web experience. We’re fans of a certain mystique which isn’t necessarily something that exists in a ‘bar that’s always closing’ and an online world ‘where people shout’. At any rate we hope you enjoy this newly formatted but still very much classic Abridged.

There is lots of Abridged activity in the coming months with the beginning of our Scarred trilogy (Nix, Trivia, Nemesis) plus The Merits of Tracer Fire, an Arts Council of Northern Ireland Commission as well as Nothing to Look Forward To But The Past, a project with Tulca and Galway2020. That’s by no means all. More news anon.

Thanks go to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland without whom Echo would not have been possible and for their support in this difficult period. And of course, to Verbal whose support has been very valuable and greatly appreciated. We’re also grateful to all our supporters in the Arts World, particularly the Golden Thread Gallery and RUA RED. Last but not least thanks to our readership, both those with us from the beginning and to those the may have just discovered us. We couldn’t do this without you.

To read the poems on computers/laptops touch and scroll the PDF. On tablets and phone you can read on full screen and scroll upwards.

0 – 60

]

]longing

]

―Sappho, trans. Anne Carson.

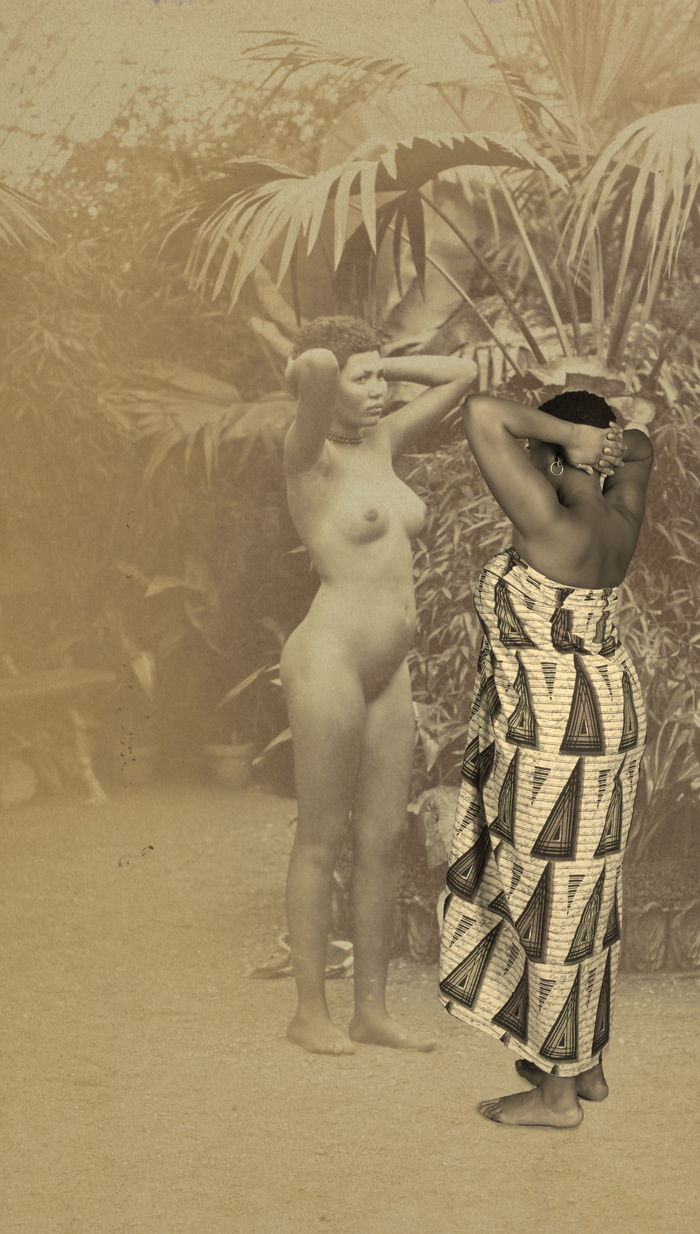

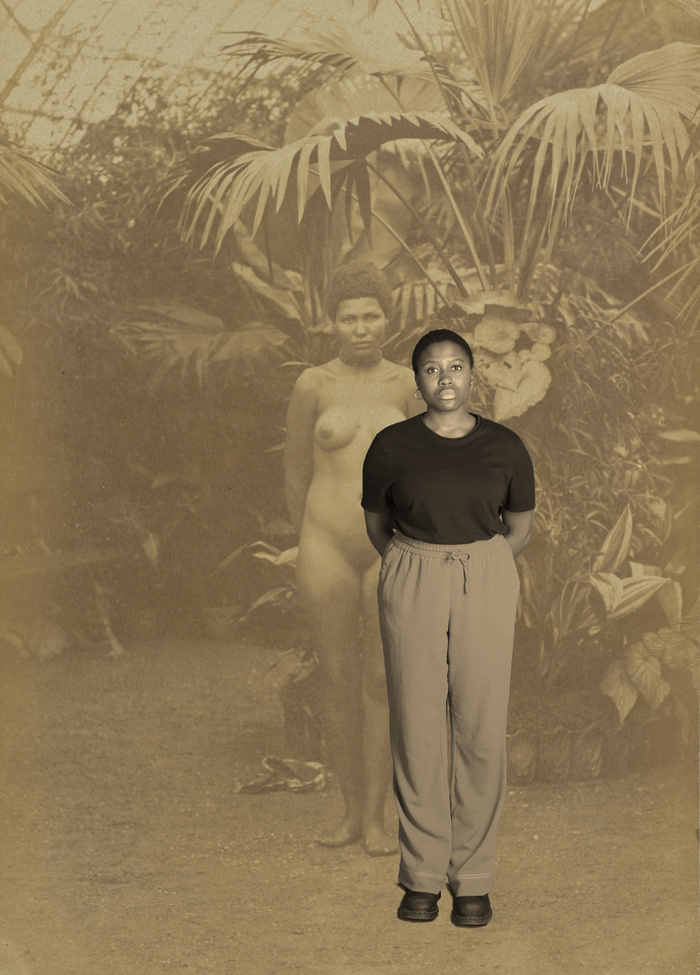

Echo knew the power of her voice to influence the actions of others. This angered those who were accustomed to being the most powerful, and resented the feeling of losing control. And so it was that Echo was punished. That is, her medium of affect was eradicated, and then some. She was left without the ability to choose her own words, to speak of her own accord. (Cor, heart). She was to remain silent until spoken to. She could only repeat fragments of what was spoken to her. And so she was condemned to grasp for her meaning in inherited speech.

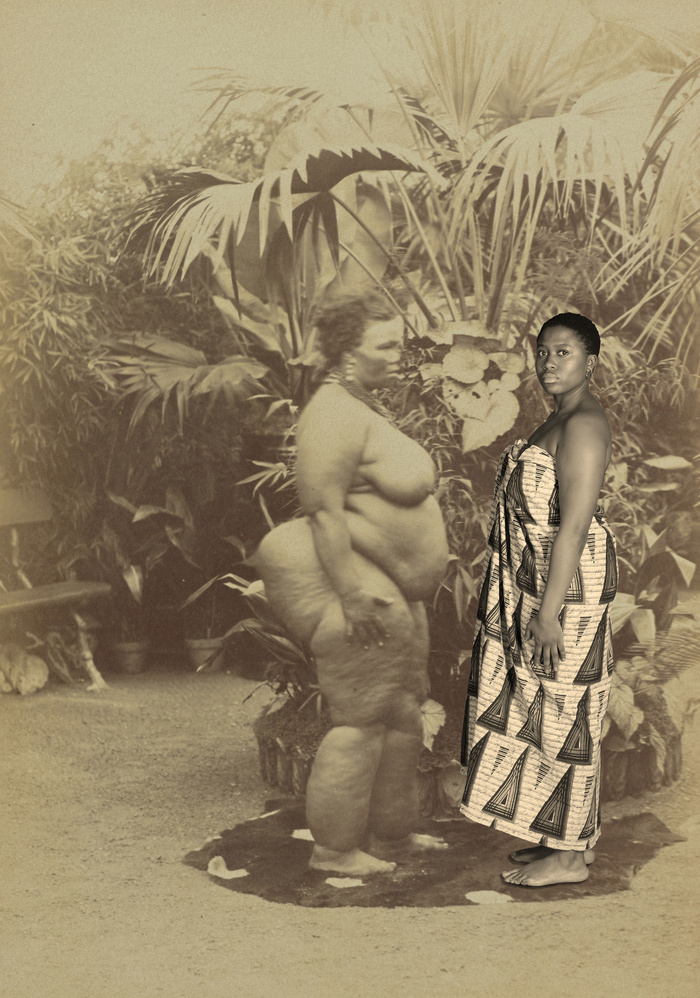

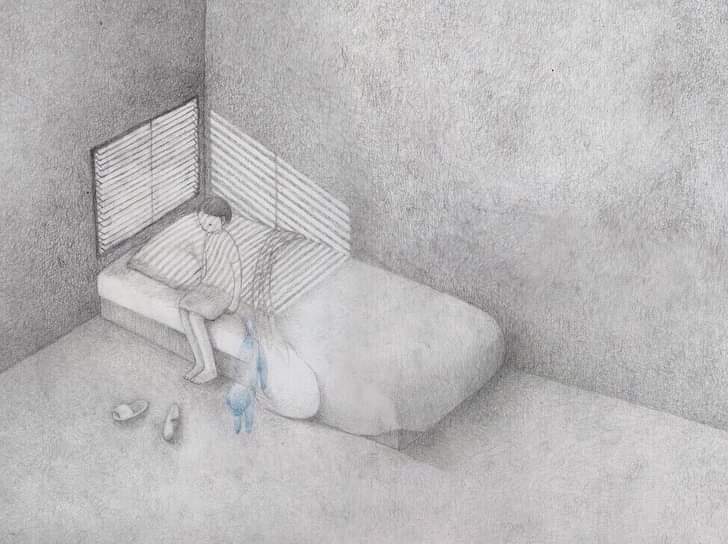

This all happened before, when Echo still had a body. It was after Narcissus came along that the loss of her words was echoed by the loss of her body (echoing her loss of his). He was the ultimate object of desire. She could only wait for his call, repurpose his words imperfectly to her own longing, to try to reach out and touch. ‘Anyone here?’ (‘Here!’) And then, rejected and shamed, speak her own annihilating pain with the words of his hate. ‘I’ll die before you’ll have your way with me!’ (‘You’ll have your way with me…’)

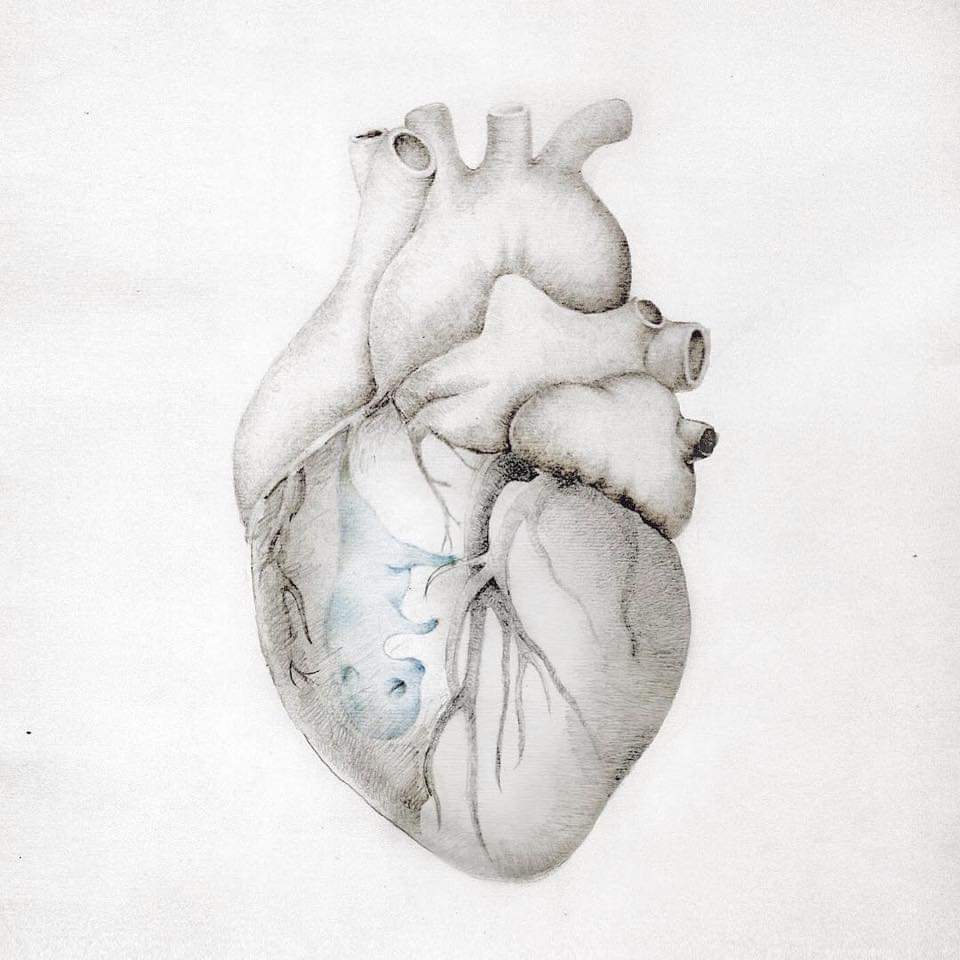

Without touch or expression, spurned from intimacy and intercourse, the erotics of language and skin by which we reinforce our existence, an isolated Echo ceases to eat is eaten up by the love-loss of desire. All that remains is a voice with the memory of a body, and all of its empathy and pleasure-pain. It lingers on and on as voices do, though it remains silent until discovered.

And as Narcissus repeats the pattern, falling in love with his own untouchable, unquenching reflection, Echo can be found in the margins, between the lines as his body too wastes away and he cries out ‘Alas dear boy who I have vainly cherished!’ (‘Alas dear boy who I have vainly cherished…’), her bodiless voice feeling into his loss as its own.

Echo’s story is a story told in brackets, an aside and counterpart to the love of a man for his own image, lending pathos and amplification to its meaning. But while Narcissus’ ‘Farewell’ (‘Farewell’) is the last word he speaks, his expired body replaced with a flower – emblematic, regenerating, sensory, silent – her voice remains, lingering forever as a haunted space in which we might discover something of ourselves, again, again, again, again.

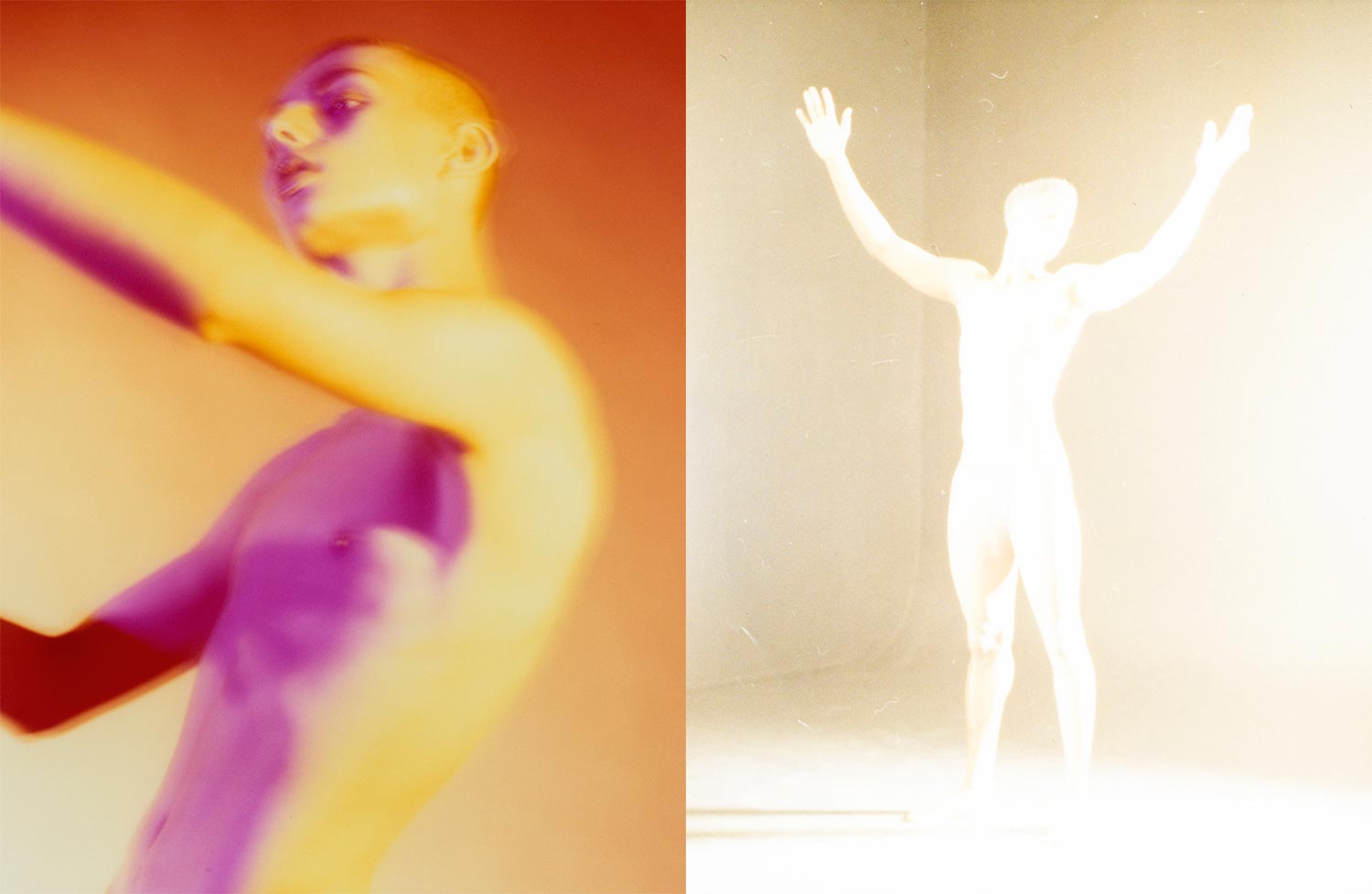

Echo’s is a story we tell ourselves to explain the inexplicable love and loss we feel calling hello down an empty passageway. It is a cave of mirrors. Narcissus echoes Echo and vice versa and again and again. In the churning it is difficult to pinpoint a beginning or an end, the origin diffuses, there is refraction. The meaning is in the reverberation, between the would-be lovers and their reflections, and beyond as our own voices continue, repeatedly, to become entangled with her emanation in the phenomenon of echo, physical and metaphorical. Nobody can understand Echo/echo as separate from themself.

In one sense Echo’s story is about the power-struggle of speech and interpretation, the limitation of language and the fluidity of truths. She is one of so many explicitly unheard women of mythology and folklore, joining Philomel and Kassandra to Anderson’s Little Mermaid. To command language is to have power over perceptions (including self-perceptions), and power systems are maintained in the architectures of language. Echo’s story raises questions about who has the power to speak, how is speaking achieved, and whether any speech act ever unhaunted, independent, free of echo?

As well as a paradigm of the disempowered, the voiceless, the repressed, Echo is an amplification of an underlying fact of communication: that we all must express ourselves in the terms of others, search for our meaning in the litter of language that surrounds us, and in the cracks of silence between fragments, submitting our slippery broken utterings to the shifting light of interpretation, hoping to be heard. At the bottom of language is the structureless mass of sound, a cry into the wilderness.

Echo amplifies the frustrations of language (and other codes), its approximation, inherited baggage, how it is all we have, how it resists our complete control, the persistent echo of the unspeakable, but also its dark depths, how so many meanings hide in the same words and phrases (silent until discovered), how repetition is never repetition, how it breaks down, how then we might hear ourselves in the cracks. There is silence within speech as there is loss within love, simultaneous, necessary.

More subtly than Persephone perhaps, Echo’s is another myth that returns us to our mouths and what we do with them, what they represent. There is speaking, and there is eating. There is language, and there is body. There is also kissing, touching, wanting, loving. There is no line between them, only a gasp for breath, an opening.

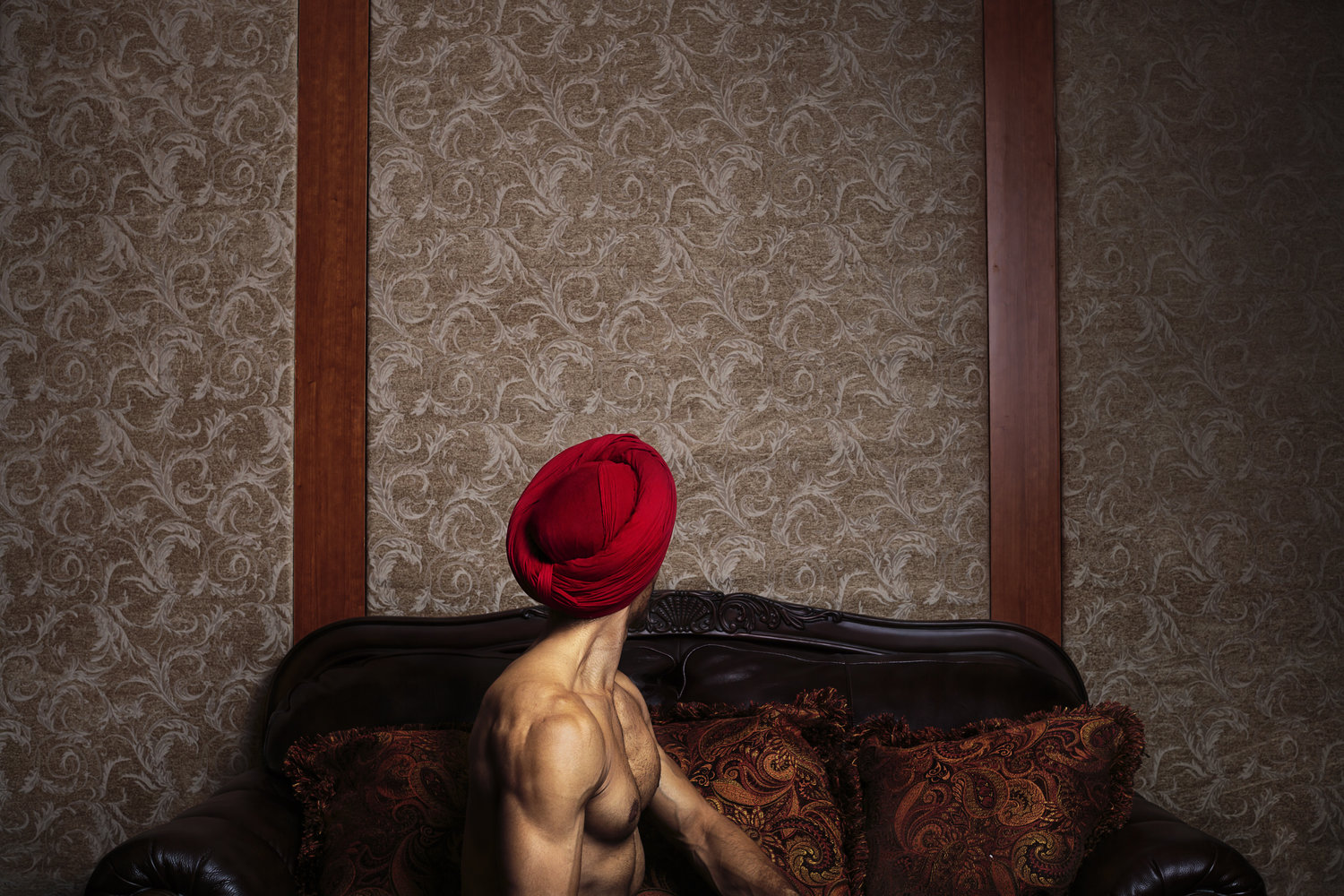

The story echoes with the complex entanglement of body and speech as the two veils that lie between self and other, rippling. We live in a world where the body is increasingly marginalised. As we move further from speech to text to digital communication, how easy it becomes to forget that speech is born of body. But echoes of the body are the ineradicable ghosts of online, weightless and mutable but there in emojis, avatars, fragments of speech. Each adheres to and defines the other, and online we depend on how language remembers the body, dissolved into each other.

‘Language is a skin: I rub my language against the other. It is as if I had words instead of fingers, or fingers at the tip of my words.’ (Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments). Touching or speaking, relations (their layering of fusing and separation) have much to do with friction. Friction is sensation, knowing we are there, knowing we are touched, touching. Friction leaves marks.

And of course, the leaving of marks is at the heart of the entangled story of Echo and Narcissus, two bodies that dissolve into permanent traces. Human knowledge that the bodies we exist as will expire, the tension between our imagination and our biology, the fact that we can think about futures beyond our mortality, defines our condition as myth making creatures. No matter how much we acknowledge the sticky blur between body and speech, we will likely always feel a tension between the flesh that expires and the voice of the mind that might be preserved, linger on.

We are driven to leave a mark, our index in the world, to be remembered in our words, our voice carried thought, encoded and preserved, somewhere. At the same time, we are also driven to love and be loved devastatingly, to plant something of ourselves in the body of another and be occupied, changed, to scar, tattoo, haunt, merge, submit and be engulfed into something defined by bodies but beyond them. Reverberating between these drives, toward love and lingering laced with oblivion, Echo’s story is a reminder that they are knotted, intractably and echoingly connected.