Happiness is a loaded weapon and a short cut is better by far…

Hello again. Welcome to Nemesis, the last (for now) of our ‘dark goddesses’ issues. We seem to have an affinity with these personae of retribution. We’ll leave it up to others to figure out why that is. We’ve been Abridged for seventeen years now. It’s probably not a good sign for the world that we are still relevant. You should probably do a ‘We Told You So’ issue you say? Next up is ‘We Told You The World Was Sick’. More news very soon.

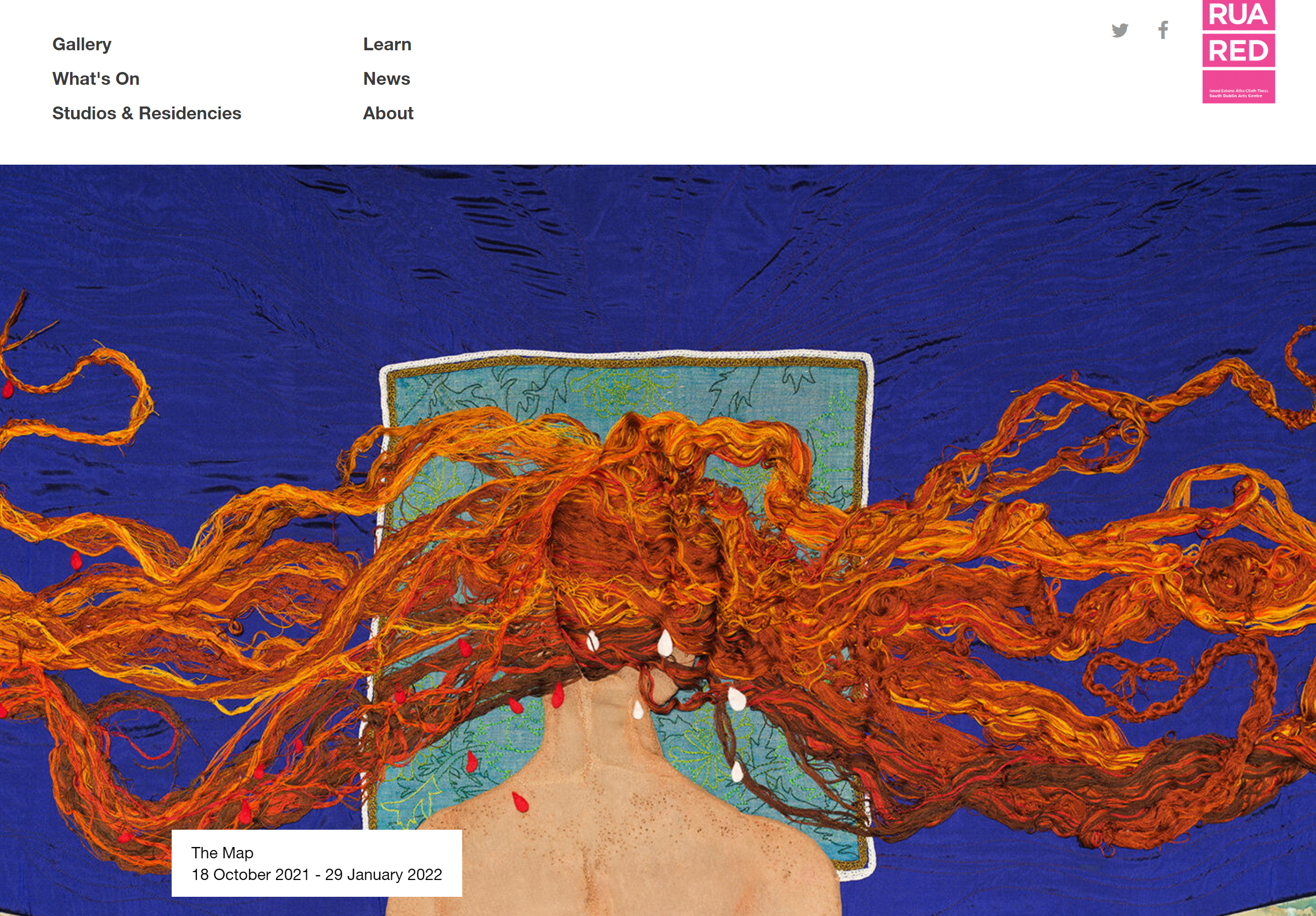

Thanks go to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for supporting this issue and for their support in this difficult period. We’re pleased to say that we’re back in print in the Autumn with Dominion, Xanadu and Axis under a You Don’t Have To Be Loved Theme. And of course, to Verbal whose support has been very valuable and greatly appreciated. We’re also grateful to all our supporters in the Arts World, particularly the Golden Thread Gallery and RUA RED. Last but not least, thanks to our readership, both those with us from the beginning and to those that may have just discovered us. We couldn’t do this without you. We wouldn’t want to.

To read the poems on computers/laptops touch and scroll the PDF. On tablets and phone you can read on full screen and scroll upwards.

ABRIDGED 0-69: NEMESIS EDITORIAL.

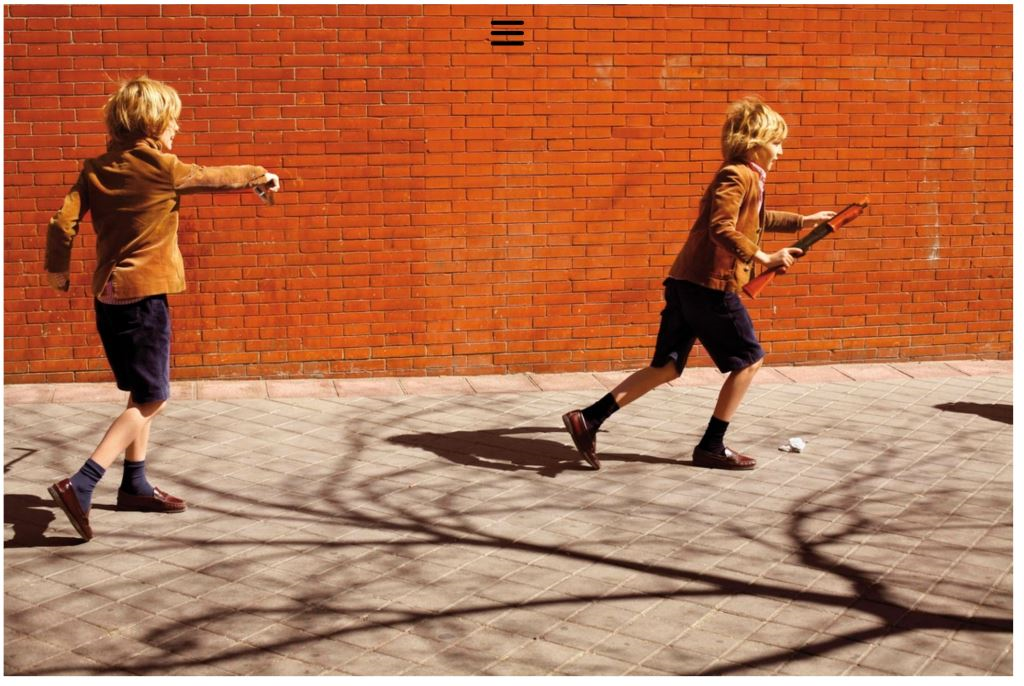

An eye for an eye. What you give is what you get. Revenge. Retaliation. Repayment. Redress. Retribution. Responsibility. Refract. Pride is a revenant; it returns, turns back on us. Actions invite their echoes. (Escalations).

Nemesis is the goddess of ‘divine retribution’. Her name, which we have dragged with us through the distorting glares of modernity, came first from the Greek ‘nemenin’: ‘to give what’s due’. She came at hubris like a flood. Correcting. As well as a sword, she carried a set of scales. A darker echo of Karma, of Fortune with her wheel, she dealt out rewards as well as punishments, raising as well as cutting down, whatever it took to restore the balance, the proper order of things.

Like death, she kept things even, returned things to before, but similarly couldn’t, as such, be called a villain. She was not the antagonist, the aggressor, but one who acted in response, when a foot was put out of line, a rung on the ladder too high. An intervention. A life for a life (or something to that effect). Her’s was a bird’s eye view.

With pride comes power, growth and triumph; jealousy, guilt, judgement, and fear. To fear is to have something to lose. Equal opportunity and levelling up is one thing. Equal limitations and levelling down, we can’t help feeling, quite another. (To have nothing is fine as long as others have less.)

Upright, creative, vulnerable and future thinking, pride is in the foundation of what we are. As such, we might be unsure about her power: Nemesis might be read as a force of equality, or of top-down oppression. It depends, perhaps, on where we happen to be reading ourselves in relation to the old seat of the gods, at one time or another.

Ambiguity invites suspicion, and our point of view is not, indifferently, from above but from our own skulls, narrowing with the press of anxiety; over time our understanding of Nemesis has focused, not on her balancing act, but on her threat to our climb, to ourselves as the heroes. It could be that what her name has become for us, it has become in a tangle with the swelling of our predominant narratives – of individualism, atheism, capitalism etc – and all of their refractions. Her name has become synonymous with ‘enemy’.

There is no hero without their nemesis. There is no self without other. (How can we expect to see without lines and contrast? That’s what we’ve been taught from our earliest lessons in how to draw the world). Without enemies, would we find ourselves without the alliances we call friends? Etymologically, ‘enemy’ comes from exactly that: ‘not-friend’. ‘Rival’, moreover, another contemporary synonym, comes from ‘rivalus’: ‘person who uses the same stream’.

Like the other ancient gods, Nemesis has largely dissolved back into how we relate to ourselves. That is, to others who are (enough) like us. Though our ages have dissolved her, we seek something of her in faces that look back at us – across seas or battlefields or screens or gardens or dinner tables – like trick mirrors. (A life for a life.)

In general, we still like our stories to have goodies and baddies, heroes and big bad wolves, even if they’re part of the same churning whole. We like stories with monsters, not just the pollution of monstrosity. Without the axis of a dividing line, we lose our balance, we get disoriented. (Keep your enemies closer). We still look for resistance to feel alive, though sometimes we aren’t comfortable with our weapons. We still say ‘I’ like it has something to do with survival.

In all of our stories – love to war, internal to interpersonal to interspecies – we want something perpetual to push against, something we can blame forever, so we can feel like we’ve a reason to keep fighting, so we can forgive ourselves for failing again and again, and so we don’t feel so alone.

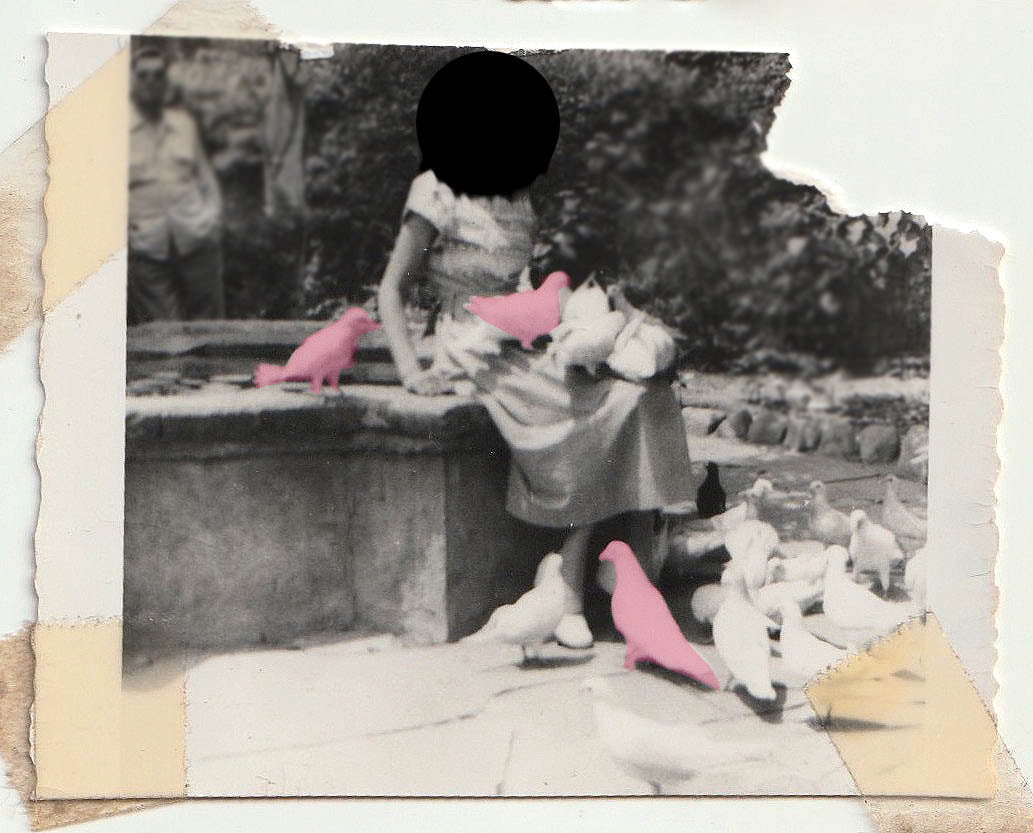

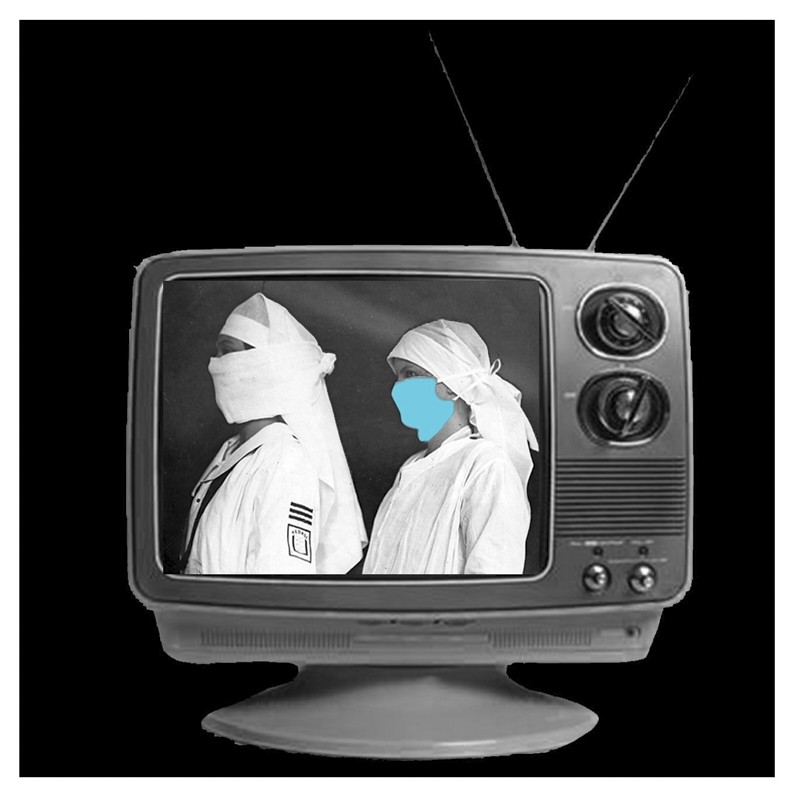

Image by Stefanie Glinski: https://www.stefanieglinski.com/

Abridged is Supported by The Arts Council of Northern Ireland.