see a body and a dream of the dead days, a following lost and blind.

Hallo again. We’ve abandoned our dark goddesses temporarily and moved on the apocryphal, that uncharted region in which unheard stories lurk, waiting for their time to go viral, to infect and mutate. And of course, to change us. Here be Dragons indeed. There are too many stories to be heard, too much ‘truth’ to be told. Where do these stories go? Are they printed on the aether, swirling around us until we absorb them knowingly or subconsciously, waiting to change our very being, who we are and how we think. Waiting to become part of our collective consciousness and ready to be called ‘common sense’.

We’re keeping the spirit of the Abridged print edition in this digital world. Therefore, you still won’t find a Contents List. Imagine instead a forest with many paths in and many paths out in which you can lose yourself and maybe even find yourself.

Next is, inevitably, Nemesis.

Thanks go to the Arts Council of Ireland for funding this issue. Thanks go to the Arts Council for their support in this difficult period. And of course, to Verbal whose support has been very valuable and greatly appreciated. We’re also grateful to all our supporters in the Arts World, particularly the Golden Thread Gallery, RUA RED and Void. Last but not least, thanks to our readership, both those with us from the beginning and to those that may have just discovered us. We couldn’t do this without you. We wouldn’t want to.

To read the poems on computers/laptops touch and scroll the PDF. On tablets and phone you can read on full screen and scroll upwards.

Abridged 0-77: Apocrypha Editorial.

We often use the word ‘apocryphal’ to cast doubt over something’s authenticity, to set it outside of the remit of the ‘true’, what is solid or confirmed. (Similar, perhaps, to how we might use the word ‘myth’). As such the apocryphal inhabits a shadowed and liminal territory. Its original connotation, however, wasn’t doubtfulness but sacredness (one notion of ultimate truth). In the world of religions and their texts ‘apocryphal’ described writings on the extreme end of the profound, those too sacred for wide readership, secret and shrouded, only to be known by initiates, by the innermost circle. This foundational definition then blends a reverence for the mysterious (something in many ways alien to us now) and a sense of anxiety about a wider public’s capacity for full and nuanced understanding. Stories (information, ideas, imaginings) can be overwhelming, can be dangerous.

The word comes from the Greek for ‘hide away’, the Latin ‘apocrypha scripta’ meaning ‘hidden writings’. In any case, apocrypha(l) has hiddenness at its root (and hidability in its echo). Later in its etymological metamorphosis ‘apocryphal’ was applied by the Christian Church to texts of dubious authorship and questionable ‘value’, possibly damaging, possibly ‘false’, frictious at the edges of doctrine. (There are ways to hide things in plain view.) We are inclined to doubt (to fear) what is left in the dark for any length of time. We like our boundaries clearly marked. And it always feels like a risk to trust others to navigate the niggles of contradiction, to cope with ambiguity, to emerge from the fog with the same images, the same convictions as you. (There is, after all, nothing certain at all about trust). What solidities might crumble if lines are allowed to blur, the greys shades allowed to show? But what will be missed by keeping things tidy, staying safely in black and white?

The Apocrypha – present, but put to the side, a separated excess – is a reminder that texts aren’t singular and whole but curated anthologies, collections of fragments stitched together, full of silences and seams. The difference between the known and unknown, the visible and invisible, is often a decision that has been made behind a closed door. How do we think about the motivations and fears (of chaos, confusion, panic, change, ambiguity, other ideas, of our own limitations and weaknesses; rational and irrational) that lie behind such decisions and behind our willingness to accept and walk the lines drawn in front of and about us? Protection of and protection from aren’t always distinct.

This is the age of the internet and its depthless universe of accessible information. In one way here we might feel like we’re beyond the canonical; here everything could be apocryphal (or is it un-apocryphal?) as vast swarms of text with uncertain authorship aren’t hidden beyond reach but available to pull into the light. But this fragmented immensity is exhausting, and makes trust – or even just seeing clearly – even more difficult. The age of the internet is also the age of curation, algorithms, and cancel culture, where ‘post-truth’ is so familiar it’s started to lose all meaning, where the muffle of erasure feels like safety, and where – faced with boundlessness – many of us are just trying to draw our own lines, to bracket some longed for territory of belief.

Abridged 0-77 ‘Apocrypha’ roams liminality across search engines, maps, caves, magazines, malls, graveyards, optical illusions, streets, living rooms, night, forests and reality tv shows, its voices speaking of the rumoured, the mythological, the coded, the forgotten, the secret, the unknown, the unspoken, the underlying, the unsure, the invisible, the interpreted, the footnoted, the marginal, the curated, the repressed, the obscured and (of course) the feared.

This issue features: Silvia Alessi, Oskar Alvarado, Clíodhna Bhreathnach, Adam Birkan, Christian Bobst, Sarah Cave, Yu-Chen Chiu, Tomaso Clavarino, Anna D’Alton, Gerald Dawe, Sharbendu De, Catherine Gander, Massimiliano Gatti, Audrey Gillespie, Oz Hardwick, Maureen Hill, Gregory Eddi Jones, Rosa Jones, Brendon Kahn, Tomasz Kawecki, Caroline King, Natasha Kinsella, Maeve MacSorley, Jagoda Malanin, Aoife Mannix, Claire Maxfield, Oak McLaughlin, Sebastian Meyer, Soso [Sorcha Ní Cheallaigh], Marco Di Noia, Jessamine O’Connor, Alanna Offield, Aldo Jose Paredes Orejuela, Louie Palu, Michelle Piergoelam, Mark Russell, Gerard Smyth, Glen Wilson, Caitlin Young and Spiros Zervoudakis.

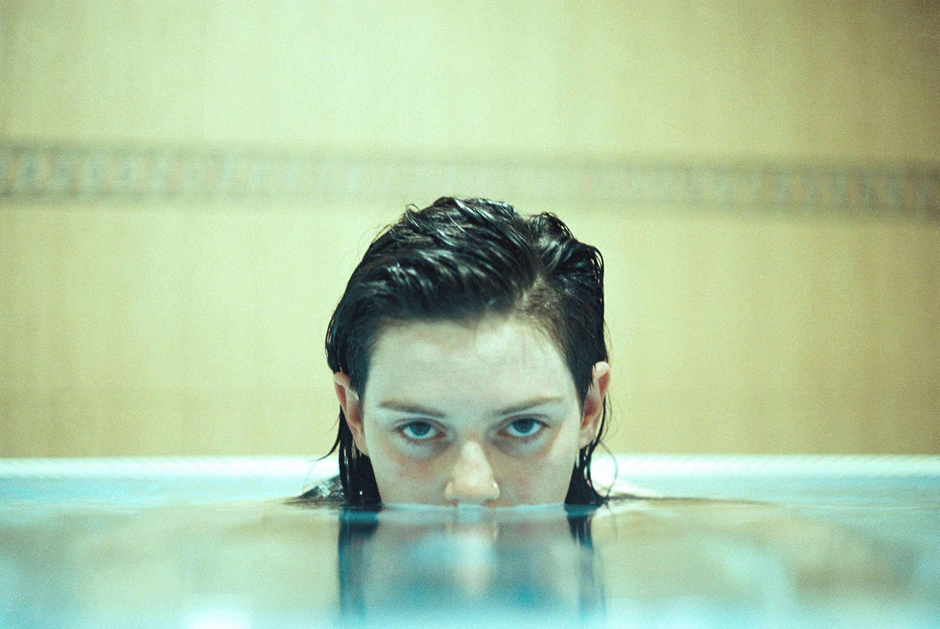

Image by Oskar Alvarado: web: https://oskaralvarado.com Instagram: @oskaralvarado.photography

Born in Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. He holds a Bachelor´s Degree in Fine Arts of the Basque Country University and resides in Barcelona where he combines his work as a Photography teacher with the production of personal works. He has been one of the winners of the Helsinki Photo Festival (Finland) in 2018 and 2020, OpenWalls Arles (France) 2020 and the winner of Art Photo Bcn 2020 in Barcelona (Spain). His work has been selected and exhibited in different international festivals such as the Voies Off Awards in Arles (France), Solar Foto Festival in Fortaleza (Brazil) , Addis Foto Fest in Addis Abeba (Ethiopia), Verzasca Foto Festival (Switzerland), Restart (Lithuania) or PHOTO IS:RAEL International Photography Festival (Israel) among others.

This issue is in collaboration with the Belfast Photo Festival’s Open Submission Call.

This issue is supported by The Arts Council of Ireland.

Abridged is supported by The Arts Council of Northern Ireland.